Zoonotic origins of COVID-19

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

| Medical response |

|

COVID-19 portal COVID-19 portal |

|

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, was first introduced to humans through zoonosis (transmission of a pathogen to a human from an animal), and a zoonotic spillover event is the origin of COVID-19 that is considered most plausible by the scientific community.[a] Human coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2 are zoonotic diseases that are often acquired through spillover infection from animals.[2]

Background

Previous emergence of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV showed that Betacoronaviruses represent a risk for emergence of diseases threatening to humans.[3][4] Increased awareness due to the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak motivated research into the potential for other coronavirus outbreaks and the animal reservoirs which could lead to them.[5] Bats, in particular, are known to harbor persistent populations of coronaviruses, and under conditions of persistent infection, coronaviruses tend to accumulate mutations that allow their receptor binding domains to interact with cross-species orthologs of the target receptors.[6] Based on serological and molecular studies, Chinese horseshoe bats were identified as the most likely reservoir for SARS-CoV-1.[7] Bats were also a likely reservoir for the related betacoronavirus MERS-CoV, though the evidence for this is less conclusive than the role of camels as a reservoir for MERS.[8] By 2010, in vitro experiments had confirmed that modifications to the spike protein receptor binding domain could enable human infection by several SARS-related coronaviruses.[9] Virologists Rachel Graham and Ralph S. Baric at that time wrote, "that the question of emergence of another pathogenic human coronavirus from bat reservoirs might be more appropriately expressed as 'when' than as 'if'."[10][better source needed]

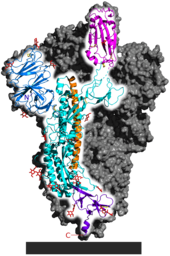

Origin in bats

The likely origin of SARS-CoV-2 from bats aligns with the origins of other coronaviruses in its genus Betacoronavirus, subgenus Sarbecovirus.[11][12][13][14] Several bat species have special cellular mechanisms to resist proinflammatory cytokines associated with Betacoronavirus virulence,[15] for example, spike proteins in SARS-related coronaviruses coevolve with bat ACE2 receptors in an evolutionary arms race.[16]

Bats, along with their viruses, have large overlapping geographic ranges in Southeast Asia,[17] and there is a particularly great concentration and diversity of bat-related coronaviruses in Southern and Southwest China.[15] The most similar known viruses to SARS-CoV-2 include bat coronaviruses RpYN06 with 94.5% identity,[15] and RmYN02 with 93% identity[18] RaTG13 was not the direct progenitor of SARS-CoV-2.[19] Temmam et al. found no serological evidence for exposure to BANAL-52 among bat handlers and guano collectors in the area of Laos where it was sampled.[20] Lytras et al. wrote that "SARS-CoV-2 can be unambiguously traced to horseshoe bats".[21] They estimated SARS-CoV-2's most recent common ancestors with RmYN02 and RaTG13 to have diverged 40 and 50 years ago, respectively.[22]

Novel features of SARS-CoV-2

The receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein has an insertion of amino acids between its S1 and S2 subunits.[23] Among Sarbecoviruses, only SARS-CoV-2 and RmYN02 have such an insertion, suggesting differences in reservoir species, intermediate hosts, or evolutionary pathway.[18] The receptor binding motif is the portion of SARS-CoV-2 that is most diverged from RaTG13.[24] The SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain is more similar to those of pangolin coronaviruses.[18] Viruses including BANAL-52 isolated from bats in Laos showed high similarity to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain in amino acid residues but less than 76.4% nucleotide identity across the spike protein.[2] The observed binding of N-acetylneuraminic acid by the NTD[25] of the spike protein and loss of that binding through mutation of the corresponding sugar binding pocket in emergent variants of concern has suggested a potential role for transient sugar-binding in the zoonosis of SARS-CoV-2, consistent with prior evolutionary proposals.[26]

Within genus Betacoronavirus, furin cleavage sites are common in subgenera Merbecovirus and Embecovirus.[27] Furin cleavage sites have independently evolved six times in different clades of Betacoronavirus.[27] Furin cleavage sites also evolved in Alphacoronaviruses and Gammacoronaviruses independently of Betacoronavirus.[27]

Furin cleavage contributes strongly to the transmissibility and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.[28] SARS-CoV-2 variants lacking the furin cleavage site are transmissible between humans, but much less effectively.[29] The furin cleavage site is sometimes described as "polybasic" on account of its particular motif of basic amino acids.[28] SARS-CoV-2 shares amino acid identity with a furin cleavage site of human ENaC α subunit.[30][31][b] Human ENaC is identical only to that of a few great apes and Pipistrellus kuhli.[32]

SARS-CoV-2 is also distinct among human coronaviruses for having a single intact ORF8 gene rather than "a" and "b" subunits.[1]

Processes of host adaptation

SARS-CoV-2 has an expanded host range compared to SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV.[33][34] SARS-CoV-2 (along with SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV) are generalist viruses, not specifically adapted to humans, meaning they have potential to spill over to many species and establish new natural reservoirs after adaptive evolutionary changes.[35]

Within a single host, a variety of single-nucleotide variations arise through random mutations and genetic drift giving rise to viral quasispecies.[36] SARS-CoV-2 mutates at a slower rate than is typical of RNA viruses.[36] The main host-derived driver of mutation is editing by APOBEC proteins.[36] Negative selection by host immune processes causes convergent evolution towards immune escape.[36] Persistence of infection is correlated with quasispecies diversity, but the direction of causality for this is unknown.[36]

Actual host susceptibility can differ significantly from in silico predictions.[35][37] The process of host adaptation has been studied in humanized mice as well as by generating mouse-adapted viral strains through serial passage.[38] Wild-type mice are only weakly susceptible to the original SARS-CoV-2 strain.[38]

Recombination

Compared to other single-stranded RNA viruses, coronaviruses have increased tendency to undergo genetic recombination, which allows them to exchange genetic material with close relatives co-infecting the same organism.[39] The origin of SARS-CoV-1 is believed to involve multiple recombination events.[40] Recombination between strains of SARS-CoV-1 is common.[41] Inferred phylogenies of SARS2-related coronaviruses might be explained by recombination.[42] Recombination between various SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern has been reported.[43]

Lytras et al. identified the SARS-CoV-2 spike open reading frame as a recombination hotspot.[44] They speculate that the SARS-CoV-2 genome may involve repeated recombination events overprinting regions that were already themselves products of recombination.[45] Temmam et al. wrote that due to the limited diffusion of bat viruses in mammals, co-infection required for recombination in mammals was unlikely.[46] Therefore, they considered it more likely that the furin cleavage site arose in a bat reservoir prior to spillover.

Selection

After cross-species transmission of a virus, rapid evolution and positive selection are expected.[47] Several studies found only weak signs of adaptive evolution early in the COVID-19 pandemic.[c] Kang et al. wrote that SARS-CoV-2 had exhibited relatively little genetic variation by 2021.[47] Tai et al. wrote that population expansion rather than positive selection explained the mutation frequency spectrum during the early pandemic.[49] Cagliani et al. wrote that the SARS-CoV-2 genome overall shows evidence of "strong to moderate" purifying selection.[50] Accessory open reading frames, especially ORF8, showed weak to neutral selection. The general lack of positive selection during the early outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 contrasted with the evolutionary course of SARS-CoV-1.[51]

Strong evidence of positive selection was found however in the spike protein S1 subunit, which contains the receptor binding domain.[24][52]

Genome instability in the spike protein is typical of coronaviruses in general, favoring the production of numerous spike protein variants.[43] The receptor binding domain is a significant factor in host tropism, or the variety of species a virus can infect.[53][54] Coronavirus adaptation to a new host often requires mutations in the receptor binding domain.[55] Kang et al. identified a single nucleotide polymorphism relative to RaTG13 in the spike protein, consistent among all of more than 180,000 SARS-CoV-2 samples, affecting glycosylation of the receptor binding domain.[56] Using a reverse genetics system to generate an ancestral-like mutant, they confirmed that the putative ancestral form of this SNP was much less transmissible in human cells.[57]

Host proteases

The majority of sarbecoviruses are not dependent on ACE2 for cell entry.[58] Guo et al. divide the sarbecoviruses into four clades, the first being ACE2-using respiratory viruses including SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2, and WIV1. Relative to clade 1, clades 3 and 4 have a one residue deletion in the receptor binding domain and diminished ability to use ACE2. Clade 2 has two deletions and does not interact with ACE2. Clades 2 through 4 are more difficult to isolate or propagate in cell culture, and consequently have been less studied. ACE2-independent infection by sarbecoviruses depends on high levels of trypsin, a digestive protein, in the host environment. Trypsin may compensate for other missing or compatible host proteases. The ubiquity of furin compared to tripsin would allow the gain of a furin cleavage site to expand viral tissue tropism.[59] Guo et al. identified clade 1 and 2 sarbecoviruses in Rhinolophus fecal samples, suggesting that both types naturally replicate in the bat digestive tract.[58] Bats with SARS-like infections in the wild showed no viral replication in respiratory droplets.[60] A fecal-oral transmission is an alternative route for some respiratory viruses.[58] No higher incidence of Sarbecoviruses has been reported in workers who come into direct contact with guano.[13] Temmam et al. found that BANAL-236, a SARS-CoV-2-related virus isolated from bats in Laos, acts as an enteric virus in macaques.[61]

Timing of spillover

In contrast to SARS-CoV-1, the initial outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 was reported in only one city.[62] Chinese epidemiological surveillance did not report any other pneumonia outbreaks in autumn 2019.[63] Graham and Baric wrote that in the case of SARS-CoV-1, virus populations circulated and adapted to civets and humans over the course of two years before the recognized outbreak.[60]

Reverse zoonosis

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from humans to animals, known as reverse zoonosis or anthroponosis, is possible.[64] Reverse zoonotic or experimental infection with SARS-CoV-2 has been reported in 31 animal species.[65] It is not believed that wildlife plays a significant role in the ongoing circulation of SARS-CoV-2 among humans.[66]

SARS-CoV-2 variants adapted to mink were found co-circulating among humans and farmed mink.[2] Mink are the only animal in Europe or North America to experience widespread SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks. Transmission from human to mink has occurred multiple times, in most cases not resulting in a sustained mink outbreak.[51] Strong evidence was seen of positive selection in mink after spillover, concentrated in the receptor binding motif.[67]

Transmission back to humans has been documented for mink, hamsters, and cats.[66] Transmission to humans from deer is suspected.[66] Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among domestic cats has been confirmed.[68]

Li et al. wrote that SARS-CoV-2 may be less able than SARS-CoV-1 to pass from humans to animals.[54]

Hypothesized intermediate hosts

In the outbreak of SARS-CoV-1, palm civets, raccoon dogs, ferret badgers, red foxes, domestic cats, and rice field rats were possible vectors.[7] Graham and Baric wrote that human and civet infections likely stemmed from an unknown common progenitor.[69] Patrick Berche wrote that the emergences of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV appeared to be sequential processes involving intermediate hosts, co-infections, and recombination.[70] In contrast with the rapid identification of animal hosts for SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, no direct animal source for SARS-CoV-2 has been found.[71] Holmes et al. wrote that the lack of intermediate host is likely because the right animal has not been tested so far.[19] Frutos et al. proposed that rather than a discrete spillover event, SARS-CoV-2 arose in accordance with a circulation model, involving repeated horizontal transfer among humans, bats, and other mammals without establishing significant reservoirs in any of them until the pandemic.[72]

Pangolins have been considered a possible reservoir of SARS-CoV-2.[73] Pangolins are sometimes sold in wet markets in China, where they are considered a culinary delicacy and a component of traditional medicine.[13] The highest sequence similarity to the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain was found in a coronavirus infecting Sunda pangolins in Guangdong province.[33] Pangolins are frequently smuggled to China.[45] Lytras et al. wrote that, consistent with a lack of reported infections of pangolins in Malaysia, they were likely infected after being trafficked into China.[45]

The SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain shares more synonymous substitutions with a pangolin-CoV than RaTG13.[74] The binding potential of SARS-CoV-2 to pangolin ACE2 however is very low.[37] The receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 has been hypothesized to originate from recombination of the relevant portion of pangolin-CoV with an RaTG13-like virus.[75]

Deer mice are highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, making them potential reservoir or intermediate hosts.[76] Raccoon dogs could be capable of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 to other animals under farm-like conditions.[68] Transmission between raccoon dogs was shown under laboratory conditions.[65] White-tailed deer are a potential vector for SARS-CoV-2.[68]

Wet market hypothesis

Spillover has been proposed to have occurred at one or more wet markets in China.[77] Wild and semi-wild game animals are commonly traded and consumed in China, and this practice has expanded in recent decades. The close contact among animals in unsanitary conditions creates the potential for diseases to thrive. In the 2002 outbreak in Guangdong, most living animals in the markets showed serological evidence of exposure to SARS-CoV-1.[70]

Many early cases were associated with the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan.[21] The first documented COVID-19 infection was in a worker at a seafood stall in the Huanan market.[78] Sequences from that patient have not been published; however, SARS-CoV-2 belonging to lineage B/L were detected in environmental samples from the patient's stall.[78] No bats or pangolins were reported to be at the market between May 2017 and November 2019. Raccoon dogs, which are hypothesized to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, were at the market.[79] A survey by He et al. in 2021 identified 102 mammal-affecting viruses in Chinese game animals, 65 of which were identified then for the first time.[80] They did not find any SARS-like viruses, but did find evidence for the transmission of a MERS-like virus from bats to hedgehogs.[80]

Between January 1 and March 30, epidemiologists from China CDC collected 457 samples from animal matter including carcasses and feces and collected 923 environmental samples. All animal samples tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.[81] SARS-CoV-2 was found in 73 environmental samples. Live virus was isolated from three samples, two of which came from stalls belonging to known patients.[81] No significant association was found between environmental virus titer and the type of product sold at particular stalls.[82] SARS-CoV-2 was identified in all four sewer wells in the market. Overground drainage from the surrounding area concentrated under the market.

One environmental sample contained lineage A/S SARS-CoV-2, while all others belonged to lineage B/L.[83] The sample containing lineage A/S also contained evidence of humans and livestock, but no wild animals.[84] Overall, wildlife including racoon dogs were detected at very low levels and mostly associated with negative samples.[85] Liu et al. wrote that there was not enough information to determine the origin of the virus.[85] In particular, they wrote that the evidence does not prove the presence of an infected raccoon dog or the occurrence of multiple zoonotic spillovers at the market as proposed by Pekar et al.

Origins of variants

The World Health Organization defines variants of concern as a variant with evidence of increase transmissibility, severity, or immune escape.[86] All variants of concern so far independently evolved from the original strain, rather than from each other.[66]

The evolution of the Omicron variant appeared to be more rapid than other variants.[55] Theories for the origin of the omicron variant include long-term circulation among humans outside areas where genetic surveillance was performed, mutation in an immunocompromised individual, or adaptation in an animal species after reverse zoonosis.[87][88] The Omicron variant is proposed to have originated in mice.[41][88]

Notes

- ^ :[1] ... "the proximal phylogenetic origin of SARS-CoV-2 and its mode of introduction into human circulation remain unclear. There is no evidence for SARS-CoV-2 having been 'engineered' in a lab. Conversely, the escape of a strain from a lab or an accidental contamination during field work cannot formally be ruled out at this stage. However, a zoonotic spillover event in nature is considered as the most plausible scenario in the scientific community"

- ^ Harrison and Sachs' analysis of the furin cleavage site have been disputed in a letter to the editor Garry, Robert F. (September 29, 2022). "SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site was not engineered". PNAS. 119 (40): e2211107119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11911107G. doi:10.1073/pnas.2211107119. PMC 9546612. PMID 36173950., with a reply from the authors Harrison, Neil L.; Sachs, Jeffery D. (November 2, 2022a). "Reply to Garry: The origin of SARS-CoV-2 remains unresolved". PNAS. 119 (45): e2215826119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11915826H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2215826119. PMC 9659384. PMID 36322733.

- ^ :[48] "Weak signs of adaptive evolution during the early phase of the epidemic of SARS-CoV-2 in humans have been observed in many studies (Chaw et al. 2020; Tang et al. 2020; MacLean et al. 2021; Martin et al. 2021)."

References

Citations

- ^ a b Balloux et al. 2022, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 15.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 23.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, pp. 20, 21, 23.

- ^ Graham & Baric 2010, p. 3135.

- ^ Graham & Baric 2010, pp. 3139–3140.

- ^ a b Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 12.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Graham & Baric 2010.

- ^ Graham & Baric 2010, pp. 3142.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Cagliani et al. 2020, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Frutos et al. 2020, p. 1.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, pp. 12, 23.

- ^ a b c Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 17.

- ^ Guo et al. 2020.

- ^ Lytras et al. 2022.

- ^ a b c Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 3.

- ^ a b Holmes et al. 2021, p. 4850.

- ^ Temmam et al. 2023, p. 8,10.

- ^ a b Lytras et al. 2022, p. 1.

- ^ Lytras et al. 2022, p. 4.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, pp. 3, 14.

- ^ a b Cagliani et al. 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Buchanan, Charles J.; et al. (2022). "Pathogen-sugar interactions revealed by universal saturation transfer analysis". Science. 377 (6604): eabm3125. doi:10.1126/science.abm3125. hdl:1983/355cbd8f-c424-4cc0-adb2-881c04ab3bf0. PMID 35737812.

- ^ Rossmann, M. G. (1989). "The Canyon Hypothesis". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (25): 14587–14590. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63732-9.

- ^ a b c Wu & Zhao 2021.

- ^ a b Hossain et al. 2021, p. 1816.

- ^ Hossain et al. 2021, p. 1817.

- ^ Anand et al. 2020.

- ^ Harrison & Sachs 2022.

- ^ Harrison & Sachs 2022, p. 4.

- ^ a b Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 14.

- ^ Li et al. 2023.

- ^ a b Li et al. 2023, p. 557.

- ^ a b c d e Biancolella et al. 2023, p. 3.

- ^ a b Frutos et al. 2020, p. 3.

- ^ a b Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 19.

- ^ Graham & Baric 2010, p. 3139.

- ^ a b Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 20.

- ^ Qian et al. 2022, p. 8.

- ^ a b Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 4.

- ^ Lytras et al. 2022, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Lytras et al. 2022, p. 6.

- ^ Temmam et al. 2023, p. 10.

- ^ a b Kang et al. 2021, p. 4393.

- ^ Tai et al. 2022, p. 4.

- ^ Tai et al. 2022, p. 8.

- ^ Cagliani et al. 2020, p. 3.

- ^ a b Tai et al. 2022, p. 2.

- ^ Qian et al. 2022.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 16.

- ^ a b Li et al. 2023, p. 554.

- ^ a b Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 21.

- ^ Kang et al. 2021, p. 4396.

- ^ Kang et al. 2021, p. 4397.

- ^ a b c Guo et al. 2022.

- ^ Jaimes, Millet & Whittaker 2020, p. 2.

- ^ a b Graham & Baric 2010, p. 3141.

- ^ Temmam et al. 2023, p. 5.

- ^ Berche 2023, p. 1,5.

- ^ Berche 2023, p. 5.

- ^ Qian et al. 2022, p. 16.

- ^ a b Reggiani, Rugna & Bonilauri 2022, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Reggiani, Rugna & Bonilauri 2022, p. 2.

- ^ Tai et al. 2022, p. 2-3.

- ^ a b c Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Graham & Baric 2010, pp. 3141, 3142.

- ^ a b Berche 2023, p. 1.

- ^ Deng, Xing & He 2022.

- ^ Frutos et al. 2021.

- ^ Frutos et al. 2020.

- ^ Cagliani et al. 2020, p. 6.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kane, Wong & Gao 2023, p. 10.

- ^ Lytras et al. 2022, p. 2.

- ^ a b Pekar et al. 2022, p. 4.

- ^ Liu et al. 2023, p. 3.

- ^ a b He et al. 2022.

- ^ a b Liu et al. 2023, p. 7.

- ^ Liu et al. 2023, p. 6.

- ^ Liu et al. 2023, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Liu et al. 2023, p. 10.

- ^ a b Liu et al. 2023, p. 12.

- ^ Qian et al. 2022, p. 13.

- ^ Qian et al. 2022, p. 14.

- ^ a b Reggiani, Rugna & Bonilauri 2022, p. 3.

Bibliography

- Anand, Praveen; Puranik, Arjun; Aravamudan, Murali; Venkatakrishnan, AJ (May 26, 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 strategically mimics proteolytic activation of human ENaC". eLife. 9. doi:10.7554/eLife.58603. PMC 7343387. PMID 32452762.

- Anderson, Kristian G.; Rambaut, Andrew; Lipkin, W. Ian; Holmes, Edward C. (March 17, 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- Balloux, François; Tan, Cedric; Swadling, Leo; Richard, Damien (June 20, 2022). "The past, current and future epidemiological dynamic of SARS-CoV-2". Oxford Open Immunology. 3 (1): iqac003. doi:10.1093/oxfimm/iqac003. PMC 9278178. PMID 35872966.

- Berche, Patrick (March 2023). "Gain-of-function and origin of Covid19". La Presse Médicale. 52 (1). doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2023.104167. PMC 10234839. PMID 37269978.

- Biancolella, Michela; Colona, Vito Luigi; Luzzatto, Lucio; Watt, Jessica Lee (July 24, 2023). "COVID-19 annual update: a narrative review". Human Genomics. 17 (1): 68. doi:10.1186/s40246-023-00515-2. PMC 10367267. PMID 37488607.

- Cagliani, Rachele; Forni, Diego; Clerici, Mario; Sironi, Manuela (April 1, 2020). "Computational Inference of Selection Underlying the Evolution of the Novel Coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2". Journal of Virology. 94 (12). doi:10.1128/JVI.00411-20. PMC 7307108. PMID 32238584.

- Canuti, Marta; Bianchi, Silvia; Kolbi, Otto; Pond, Sergei L.K. (March 16, 2022). "Waiting for the truth: is reluctance in accepting an early origin hypothesis for SARS-CoV-2 delaying our understanding of viral emergence?". BMJ Global Health. 7 (3): e008386. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008386. PMC 8927931. PMID 35296465.

- Cohen, Jon (August 19, 2022). "Anywhere but Here". Science. 377 (6608): 805–809. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..805C. doi:10.1126/science.ade4235. PMID 35981032. S2CID 251670601.

- Fernando, Christine; Mumphrey, Cheyanne (December 20, 2020). "Racism targets Asian food, business during COVID-19 pandemic". PBS News Weekend.

- Deng, Shanjun; Xing, Ke; He, Xionglei (February 2022). "Mutation signatures inform the natural host of SARS-CoV-2". National Science Review. 9 (2): nwab220. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwab220. PMC 8690307. PMID 35211321.

- Eban, Katherine (June 1, 2023). "Inside the COVID Origins Raccoon Dog Cage Match". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023.

- Frutos, Roger; Pliez, Olivier; Gavotte, Laurent; Devaux, Christian A. (October 6, 2021). "There is no "origin" to SARS-CoV-2". Environmental Research. 207. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112173. PMC 8493644. PMID 34626592. S2CID 238412878.

- Frutos, Roger; Serra-Cobo, Jordi; Chen, Tianmu; Devaux, Christian A. (August 5, 2020). "COVID-19: Time to exonerate the pangolin from the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to humans". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 84. Bibcode:2020InfGE..8404493F. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104493. PMC 7405773. PMID 32768565. S2CID 220971074.

- Ge, Xing-Yi; Li, Jia-Lu; Yang, Xing-Lou; Chmura, Aleksei A. (October 30, 2013). "Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor". Nature. 503 (7477): 535–538. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..535G. doi:10.1038/nature12711. PMC 5389864. PMID 24172901. S2CID 4464714.

- Goodman, Brenda (July 11, 2023). "Scientists at House hearing refute claims they were bribed and influenced to deny Covid-19 'lab leak' theory". CNN.

- Graham, Rachel L.; Baric, Ralph S. (April 2010). "Recombination, Reservoirs, and the Modular Spike: Mechanisms of Coronavirus Cross-Species Transmission". Journal of Virology. 84 (7): 3134–3146. doi:10.1128/JVI.01394-09. PMC 2838128. PMID 19906932.

- Guo, Hua; Hu, Bing-Jie; Yang, Xing-Lou; Zeng, Lei-Ping (September 29, 2020). "Evolutionary Arms Race between Virus and Host Drives Genetic Diversity in Bat Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus Spike Genes". Journal of Virology. 94 (20). doi:10.1128/JVI.00902-20. PMC 7527062. PMID 32699095. S2CID 220716415.

- Guo, Hua; Li, Ang; Dong, Tian-Yi; Su, Jia (November 21, 2022). "ACE2-Independent Bat Sarbecovirus Entry and Replication in Human and Bat Cells". Virology. 13 (6): e0256622. doi:10.1128/mbio.02566-22. PMC 9765407. PMID 36409074.

- Harrison, Neil L.; Sachs, Jeffery D. (May 19, 2022). "A call for an independent inquiry into the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus". PNAS. 119 (21): e2202769119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11902769H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2202769119. PMC 9173817. PMID 35588448.

- He, Wan-Ting; Hou, Xin; Zhao, Jin; Sun, Jiumeng (February 16, 2022). "Virome characterization of game animals in China reveals a spectrum of emerging pathogens". Cell. 185 (7): 1117–1129.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.014. PMC 9942426. PMID 35298912.

- Holmes, Edward C.; Goldstein, Stephen A.; Rasmussen, Angela L.; Robertson, David L. (September 16, 2021). "The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review". Cell. 184 (19): 4848–4856. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. PMC 8373617. PMID 34480864.

- Hossain, Golzar; Tang, Yan-dong; Akter, Sharmin; Zheng, Chunfu (December 22, 2021). "Roles of the polybasic furin cleavage site of spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 replication, pathogenesis, and host immune responses and vaccination". Journal of Medical Virology. 94 (5): 1815–1820. doi:10.1002/jmv.27539. PMID 34936124. S2CID 245430230.

- Jaimes, Javier A.; Millet, Jean K.; Whittaker, Gary R. (June 26, 2020). "Proteolytic Cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and the Role of the Novel S1/S2 Site". iScience. 23 (6). Bibcode:2020iSci...23j1212J. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101212. PMC 7255728. PMID 32512386.

- Kane, Yakhouba; Wong, Gary; Gao, George F. (February 2023). "Animal Models, Zoonotic Reservoirs, and Cross-Species Transmission of Emerging Human-Infecting Coronaviruses". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 11: 1–31. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-020420-025011. PMID 36790890. S2CID 256869353.

- Kang, Lin; He, Guijuan; Sharp, Amanda K.; Wang, Xiaofeng (July 6, 2021). "A selective sweep in the Spike gene has driven SARS-CoV-2 human adaptation". Cell. 184 (17): 4392–4400.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.007. PMC 8260498. PMID 34289344.

- Kumar, Sudhir; Tao, Qiqing; Weaver, Steven; Sanderford, Maxwell (August 8, 2021). "An Evolutionary Portrait of the Progenitor SARS-CoV-2 and Its Dominant Offshoots in COVID-19 Pandemic". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 38 (8): 3046–3059. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab118. PMC 8135569. PMID 33942847.

- Li, Hongying; Mendelsohn, Emma; Zong, Chen; Zhang, Wei (September 2019). "Human-animal interactions and bat coronavirus spillover potential among rural residents in Southern China". Biosafety and Health. 1 (2): 84–90. doi:10.1016/j.bsheal.2019.10.004. PMC 7148670. PMID 32501444.

- Li, Meng; Du, Juan; Liu, Weiqiang; Li, Zihao (January 23, 2023). "Comparative susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV across mammals". ISME. 17 (4): 549–560. Bibcode:2023ISMEJ..17..549L. doi:10.1038/s41396-023-01368-2. PMC 9869846. PMID 36690780.

- Liu, William J.; Liu, Peipei; Lei, Wenwen; Jia, Zhiyuan (April 5, 2023). "Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 at the Huanan Seafood Market". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06043-2. PMID 37019149. S2CID 257983307.

- Lytras, Spyros; Hughes, Joseph; Martin, Darren; Swanepoel, Phillip (February 8, 2022). "Exploring the Natural Origins of SARS-CoV-2 in the Light of Recombination". Genome Biology and Evolution. 14 (2). doi:10.1093/gbe/evac018. PMC 8882382. PMID 35137080.

- Lubinski, Bailey; Whittaker, Gary R (August 2023). "The SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site: natural selection or smoking gun?". The Lancet Microbe. 4 (8): e570. doi:10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00144-1. PMC 10205058. PMID 37236215.

- MacLean, Oscar A.; Lytras, Spyros; Weaver, Steven; Singer, Joshua B. (March 12, 2021). "Natural selection in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in bats created a generalist virus and highly capable human pathogen". PLOS Biology. 19 (3): e3001115. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001115. PMC 7990310. PMID 33711012.

- McCarthy, Simone; Baptista, Eduardo (October 15, 2021). "Science turns nasty in Covid-19 origins argument on Twitter". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024.

- Menachery, Vineet D.; Yount, Boyd L. Jr.; Sims, Amy C.; Baric, Ralph S. (March 14, 2016). "SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence". PNAS. 113 (11): 3048–3053. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.3048M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517719113. PMC 4801244. PMID 26976607.

- Palmer, James (January 27, 2020). "Don't Blame Bat Soup for the Coronavirus". Foreign Policy.

- Pekar, Jonathan E.; Magee, Andrew; Parker, Edyth; Moshiri, Niema (July 26, 2022). "The molecular epidemiology of multiple zoonotic origins of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 377 (6609): 960–966. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..960P. doi:10.1126/science.abp8337. PMC 9348752. PMID 35881005.

- Qian, Zhaohui; Li, Pei; Tang, Xiaolu; Lu, Jian (March 1, 2022). "Evolutionary dynamics of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 genomes". Medical Review. 2 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1515/mr-2021-0035. PMC 9047652. PMID 35658106.

- Reggiani, Alessandro; Rugna, Gianluca; Bonilauri, Paolo (December 15, 2022). "SARS-CoV-2 and animals, a long story that doesn't have to end now: What we need to learn from the emergence of the Omicron variant". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 9. doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.1085613. PMC 9798331. PMID 36590812.

- Smith, David (February 28, 2023). ""It's just gotten crazy": how the origins of Covid became a toxic US political debate". The Guardian.

- Tai, Jui-Hung; Sun, Hsaio-Yu; Tsung, Yi-Cheng; Li, Guanghao (August 8, 2022). "Contrasting Patterns in the Early Stage of SARS-CoV-2 Evolution between Humans and Minks". Journal of Virology. 94 (12). doi:10.1128/JVI.00411-20. PMC 7307108. PMID 32238584.

- Temmam, Sarah; Montagutelli, Xavier; Herate, Cécile; Donati, Flora (April 5, 2023). "SARS-CoV-2-related bat virus behavior in the human-relevant models sheds light on the origin of COVID-19". EMBO Reports. 24 (4): e56055. doi:10.15252/embr.202256055. PMC 10074129. PMID 36876574.

- Temmam, Sarah; Vongphayloth, Khamsing; Baquero, Eduard; Munier, Sandie (February 16, 2022). "Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells". Nature. 604 (7905): 330–336. Bibcode:2022Natur.604..330T. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04532-4. PMID 35172323. S2CID 246902858.

- Tobias, Jimmy (July 12, 2023). "Amid Partisan Politicking, Revelations on a Covid Origins Article". The Nation.

- Willman, David (September 7, 2023). "The US quietly terminates a controversial $125m wildlife virus hunting programme amid safety fears". BMJ. 382: 2002. doi:10.1136/bmj.p2002. PMID 37678902. S2CID 261557718.

- Willman, David; Warrick, Joby (April 10, 2023). "Research with exotic viruses risks a deadly outbreak, scientists warn". Washington Post.

- Wu, Yiran; Zhao, Suwen (January 2021). "Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses". Stem Cell Research. 50. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2020.102115. PMC 7836551. PMID 33340798.

- "An acrimonious debate about covid's origins will rumble on". The Economist. June 26, 2023. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023.